The Landscapes of Kim Berman

Wilhelm van Rensburg

Senior Art Specialist & Head Curator

Strauss & Co

Kim Berman’s landscapes of the 1980s and early 90s were made under the then State of Emergency, a very turbulent time in the death throes of apartheid in South Africa. Turbulence, an integral part of printmaking, Berman’s preferred medium in which her political landscapes were executed, had an urgency about it, and a veritable life of its own, literally multiplying editions off the printing press to find their way into the world, to spread South Africa’s horrific news.

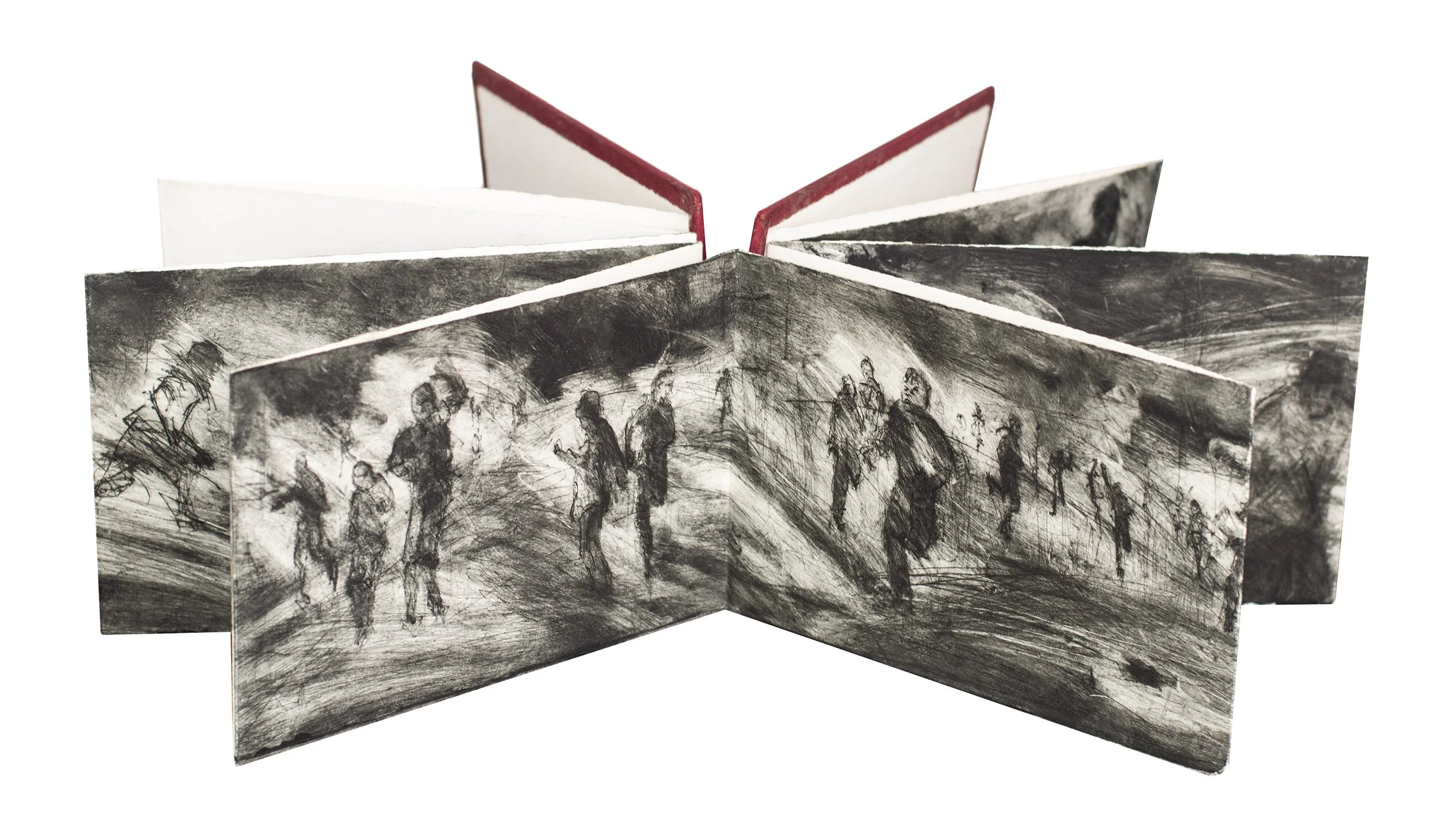

Berman’s linocut portraits of banned activists at the time were used to make posters as forms of resistance (the Unnamed Heroes woodcuts, for example), and to illustrate such publications as Frontline Southern Africa: Destructive Engagement, 1988. She also assembled these prints into a series of artist’s books. The common denominator: the consciousness in the country at the time about the urgency of relentless resistance made Berman’s representation of the landscape an indisputable political text.

Frontline Southern Africa: Destructive Engagement, 1988, Artist’s book

Much earlier, while an honours student at Wits University in 1981, she used a torn poster of the activist Neil Aggett, killed in detention, to make the photo-etching Remember Neil Agget. Berman saw her role as a visual literacy activist. Once in self-exile in Boston, and an MFA student at the School of Museum of Fine Art, (a promoter of Abstract Expressionism at the time), she was seen as a maverick for incorporating documentary photographs of brutality into her work. Her ‘political texts’ had their ‘histories’ in the works of Francesco Goya, Käte Kollwitz, and the work of the German expressionists during World War I. Berman became an integral part of Resistance Art in the South African art history of the 1970s and 80s.

Unnamed Heroes, 1990, Artist’s book of woodcuts

Remember Neil Agget and Freedom Now 1981, Photo-etchings

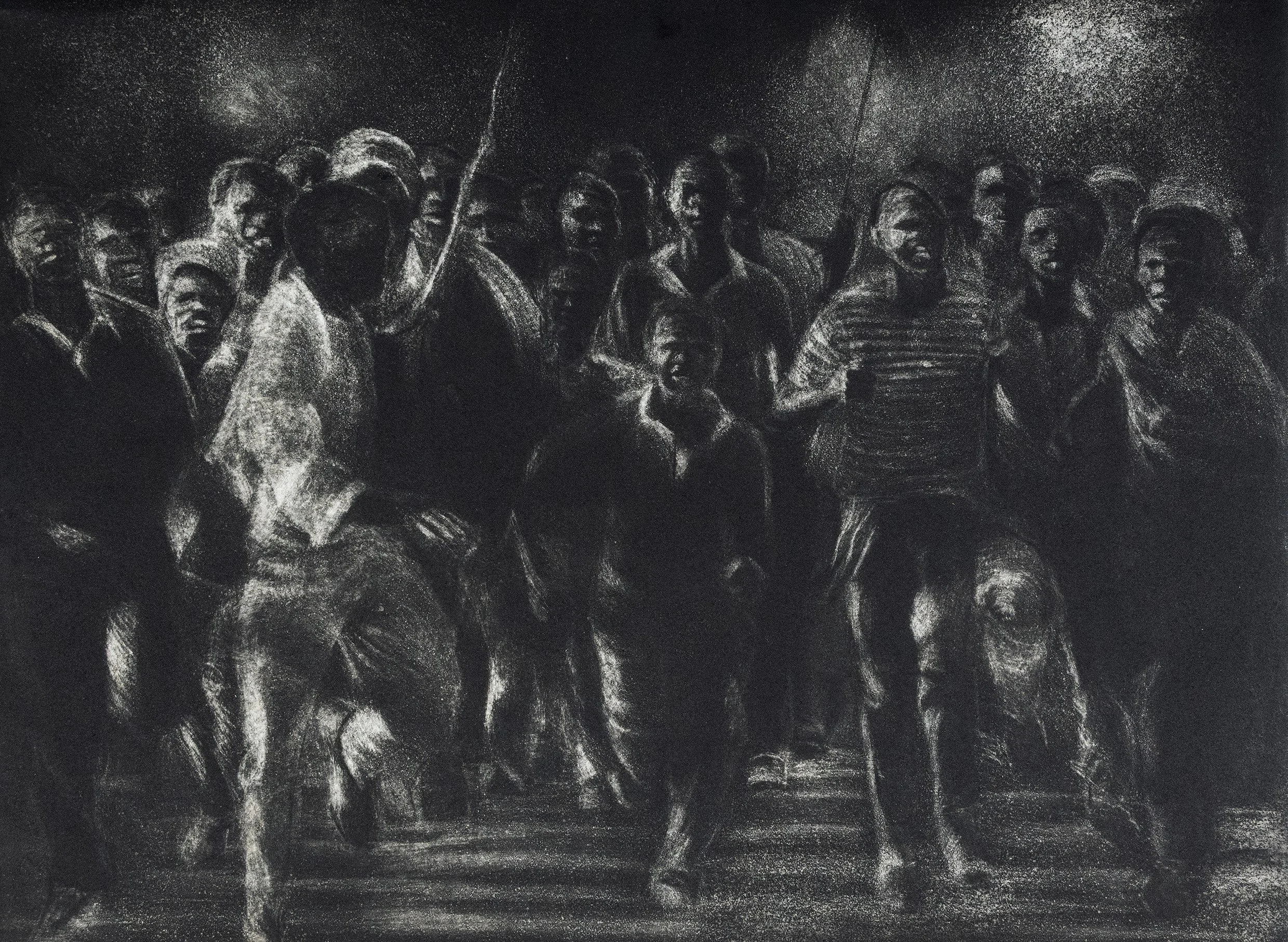

Berman’s political landscapes of this era depict scenes of horror: attacks by right wing vigilantes, police brutality of chasing, sjambokking and teargassing protesters, killing them at random, but also of protesters who, in turn, turning on their torturers, pelted the police and their ominous-looking vehicles with stones, bottles, and the like. She drew her images from photographs from Afrapix - a South African photography collective that was banned in South Africa during the State of Emergency – which were smuggled out the country to Boston.

Mabangalala series, 1997, 2 out of 6 Aquatint mezzotints

These prints, mainly dark and brooding mezzotints, capture the spirit of the era perfectly.

Berman’s landscapes of this era are essentially cityscapes teeming with activity, not the expected rural idyll of what is commonly understood by landscape painting. Joseph Addison’s old diction, “A spacious Horizon is an Image of Liberty”[1], has an ironic ring in this regard: the South African land and its implied landscape was not free at all at the time. Berman’s landscapes are more aligned with Waldo Emmerson’s statement that the role of the artist is ‘seeing’ the holistic image of a landscape, not individual properties of the ‘rightful’ owners[2]. Berman is relentless in presenting us with a landscape under siege, the whole picture of the land under apartheid, transcending local particulars, co-ordinating and unifying the real intent of the Struggle. Another early photo-etching uses the graffiti text “Freedom Now”.

Art, then, made under siege, seems to be a trope under discussion from the very early history of art. In a recent publication,Art in a State of Siege[3], Joseph Koerner invokes Hieronymus Bosch and Peter Bruegel, as well as Max Beckmann, but also focuses on William Kentridge’s triptych,Art in a State of Grace, Art in a State of Siege, and Art in a State of Hopethat resonates well with the body of work created by Berman in the 80s and early-90s.

William Kentridge Art in a State of Grace, Art in a State of Siege, and Art in a State of Hope, 1988, Screenprint triptych

It is long thought that if a static medium like painting were to convey an historic event effectively, it must present the most ‘pregnant’ moment in the narrative. This is exactly what Berman’s prints of the 1980s did: showing the anti-apartheid activists in a tumultuous state, fighting for their own lives and for the liberty of the land. Kentridge’s triptych, on the other hand, depicts the perpetrators: the complacent white bourgeoisie, ravenous capitalists, and duplicitous politicians.

Using a large-scale screenprint medium for this triptych, Kentridge’s first image, Art in A State of Grace,portrays a bespectacled woman, wearing pearls, and quite oblivious of the catfish on her head, to symbolise the ‘graceful’, aesthetically pleasing impressionist and post-impressionist art produced in peaceful times by such artists as J.E.A. Volschenk and J.H Pierneef. The second image, Art in a State of Hope, depicts the back of a gigantic head of a woman in the shape of an old-fashioned mechanical fan, the caption referencing the Russian Constructivist Vladimir Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International signifying a celebration to the working class, a transformation, if not a revolution; and the third image, Art in a State of Siege, shows the greedy, pinstriped, tycoon-type capitalist, namely Soho Eckstein, a character often appearing in Kentridge’s early stop-frame animation video films.

In a lecture, soon after the then Prime Minister P.W. Botha had declared a State of Emergency on 12 June 1986, Kentridge acknowledges his ambivalent position in South Africa as “neither active participant [in the struggle] nor disinterested observer”[4], continuing to say his “optimism is kept in check and nihilism is kept at bay”[5]. Berman would have none of that; she plunged herself into activism and art making in a significant way. Berman and Kentridge, however, do share an inherent experience of trauma of and at the time.

Koerner raises an important debate in this regard in art history, asking to what extent is the meaning of an artwork bound up with the circumstances of its creation, or its ‘historicity’, and to what extent does its significance develop unevenly over time, or ‘anachronically’, in other words in multiple ways of reception and interpretation. Put differently, what is the significance of Berman’s 1980s and early 90s political landscape today? Has it changed at all? Is it worse than before? What are the mitigating circumstances? Berman’s retrospective exhibition here of more than four decades of creative work shows the ever-evolving landscape, at times burning, at others, mourning, but never complacent. Ultimately, the state of urgency of her work of that time was vindicated; but now quietly relentless, her ‘damaged’ landscapes continue to show the ongoing struggle for social justice after the fall of apartheid.

State of Emergency, 1986, Artist’s book, drypoints

[1] Joseph Addison (1712) The Spectator, 23 June 1712.

[2] Ralph Waldo Emmerson (1836), quoted in Malcolm Andrews (1999) Landscape and Western Art. Oxford University Press, page 157.

[3] Joseph L. Koerner (2025) Art in a State of Siege. Princeton University Press.

[4] Willaim Kentridge (1988) ‘Landscape in a State of Siege’. Stet literary magazine, Volume 5 Number 3. Johannesburg, pages 15 – 18.

[5] Ibid.