Musings and Reflections on Kim Berman’s Printmaking, specifically, two solo exhibitions at Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg:

1999: Kim Berman: A Decade of Work, and

2002: Kim Berman: New Works.

This essay was compiled by Mandy Conidaris from audio recordings by curator Neil Dundas.

Early in her career, Kim Berman left South Africa to study, teach, and further her own learning in the USA. At both Tufts and the Museum School of Fine Arts in Boston, she focused on large scale printing and especially variations of monotype printing, using South African landscapes as both literal and allegorical subject matter.

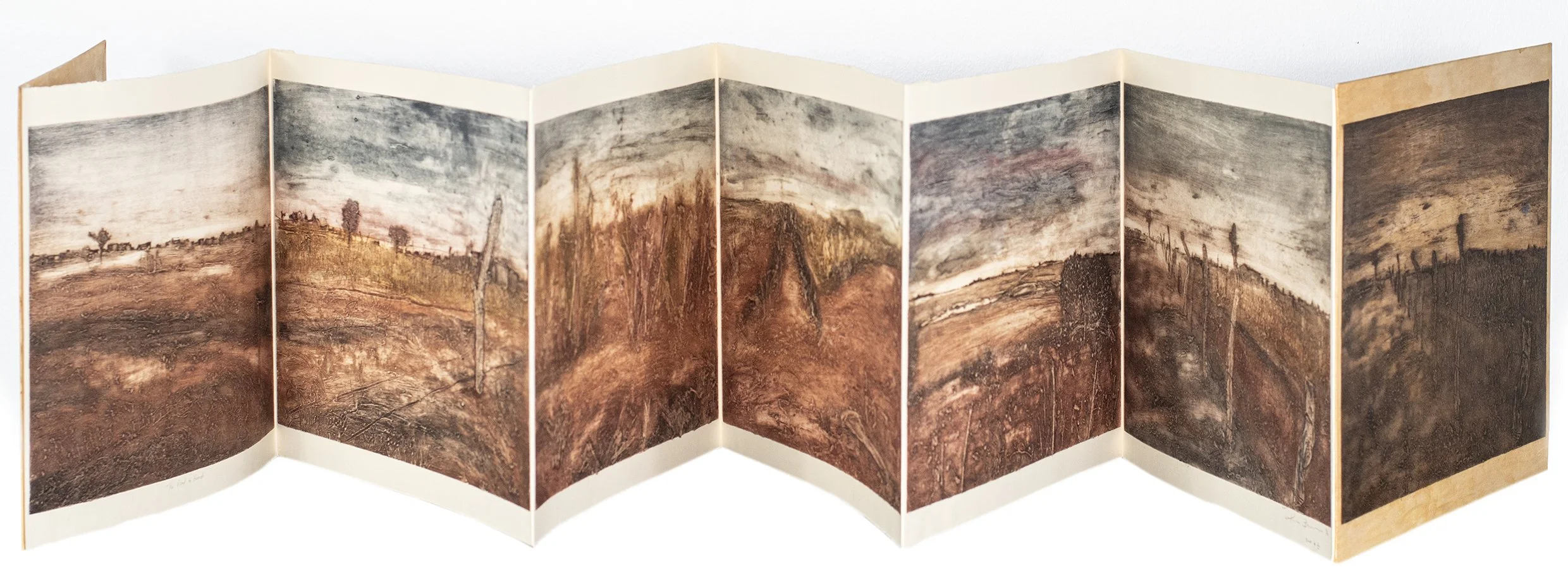

I wanted to contribute some musings from notes I made while relooking at Berman’s earlier prints. First, her beautiful folding leporello,a printed book titled The Road to Huhudi, made in 1993. This work firmly established my appreciation for her deftness and ability to create a landscape that works well over this long-form, concertina format. Kim’s handling of printed colour wiping is impressive - she does not wipe away all the ink from the plate but also moves some ink across the whole work, in a long sweep, continuing the curvature of an horizon line.

The Road to Huhudi, 1993, Artist’s book

These prints are not just documentary; they owe a lot to South African traditions in landscape painting. Notably they reveal such a sparse, desert-like landscape and show a sky which appears to evolve and bring menace in cloud and then pass over. For me, they preface the scorched earth in Berman’s Fires of the Truth Commission works. And as always, there is a beautiful allegory around how land in South Africa holds our emotions in thrall - how in fact the land is so much a receptacle of collective memory, or is the holder of jointly owned memory, of a people who have gone through trial and tribulation time and again.

It is remarkable to see artwork which truly has the unique stamp of an artist; but which is not only Kim Berman’s palette of the colours for our land and sky. It also evokes paintings of the big-sky country in 20th century South African painting and yet points us to her particular kind of mark making, revealed in monotype prints. Individual and unmistakeable. Here, too, is her understanding through the printing process, of how this pressing of paper onto plate, this heavy physical pressure, can lead to what Robert Hodgins, (among others), would refer to as the ‘happy accident’ for printers. In other words, a reference to some willing loss of control, some need to accept happenstance in the making of prints.

Berman demonstrates that she can make allowance for some slight imperfection to appear, if compared to the original image created on her plate, but be welcomed and suitably purposed. Her understanding of that, added to her control of different kinds of inks and paint transfers, adapting and using them to answer her intent, truly shows just what a master printer she is. Seeing this special fold-out concertina book, Road to Huhudi, for the first time, I recall being amazed, thinking how such delicacy of colour and nuance in such powerful imagery reveals a very differently talented printmaker at work.

The Road to Huhudi (page 1), 1993, Artist’s book

Berman’s work took time to move from monochrome into colour, after her return to South Africa. She favoured always muted, earthy pigments. In the series Sunflowers in Mourning, she looked at rural women through the eyes of a woman artist, focused on how women were farming through tough economic times, including a cycle of severe drought, highlighting the way they were marginalised, almost excommunicated from cities and the access to resources that urban life might give. Sunflowers in Mourning offers a perception that drought would colour the way people worked and saw themselves in relation to the landscape. Earth and sky are still very much the centre of things, but present unvarnished the results of drought - scorched earth ending where the sunflowers, having bloomed, germinated and cast their seeds, are left drying and darkening in the sky.

Two pages from The Women of Madibogopane 1993, Artist’s book

(Left) The Prayer of the Sunflowers

(Right) The Women of Madibogopane

In this work there is a sense of foreboding, of questioning ‘what is to come in the wake of such damaged earth?’. The potential trauma South Africa was heading for is seen in the work. Following decades of oppressive rule, the enforced separation of peoples, States of Emergencies in the 1980s and that “crossing the Rubicon” in the 1990s, the viewer is shown storms brewing and uncertainty. The artist’s works later acknowledge the liberation of Mandela but also recognised the way in which history being confronted also sparked conflict again. Even as the laws of oppression were receding, the view on the landscapes of South Africa became even more highly contested. Berman’s theme of landscape under grave pressure, under enduring hardship, is an allegory for both the state of mind of the country, and the state of mind of a printmaker wanting to work with colour but understanding its reticence in what she reveals.

Unburied Dead I and II … Memorial Landscapes, 2001, Monotypes

Looking at Kim’s writing, she describes her studies at the Museum School of Fine Arts in Boston, with reference to Clement Greenberg and how the ideas of the time favoured the use of Abstract Expressionism in covering subjects metaphorically or allegorically – especially if a subject held some inherent risk if relying on graphic realism and representation. This was especially relevant to South Africans who lived and worked abroad in self-imposed exile, or who lived in the country while enduring direct oppression of those politically active in anti-apartheid art movements.

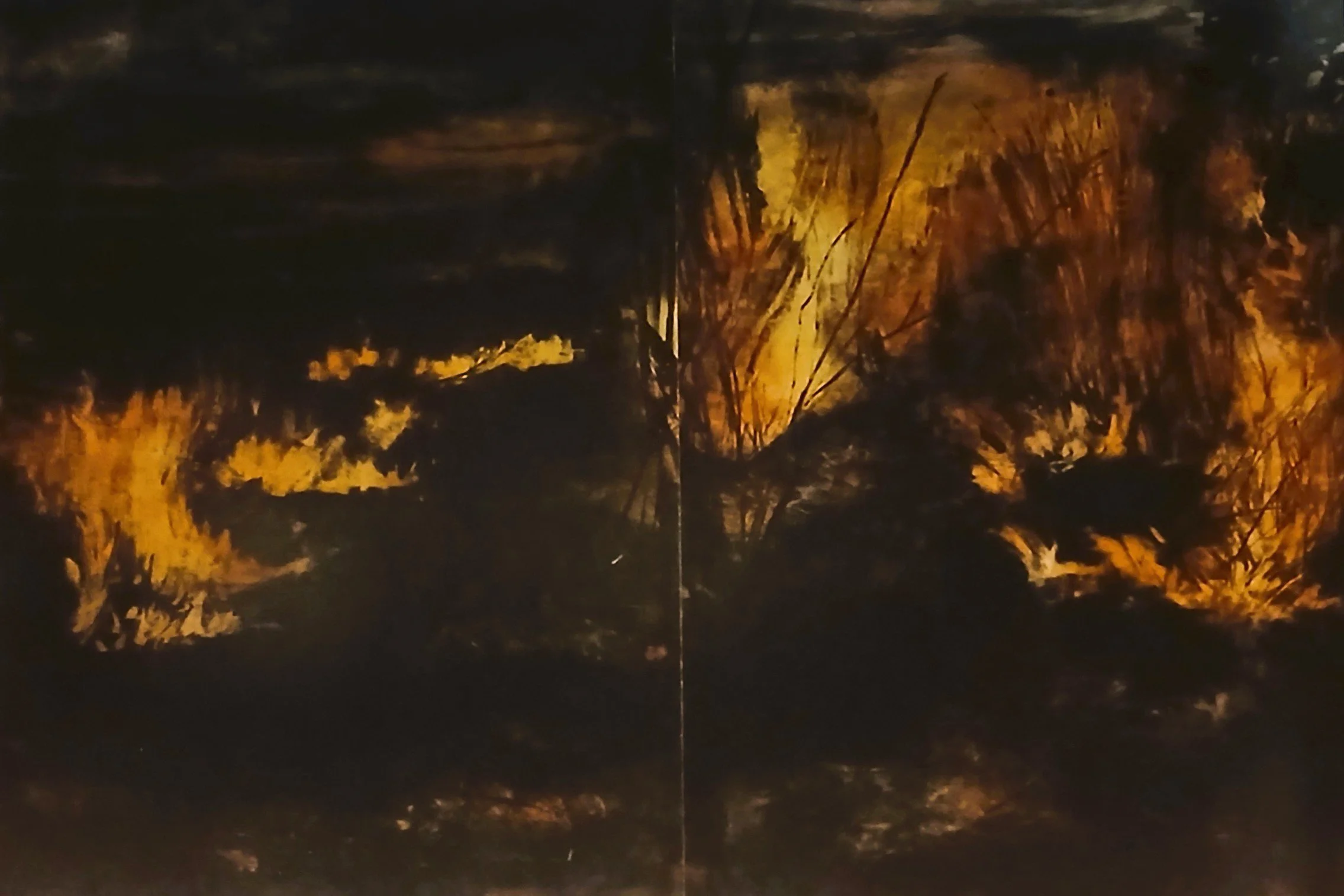

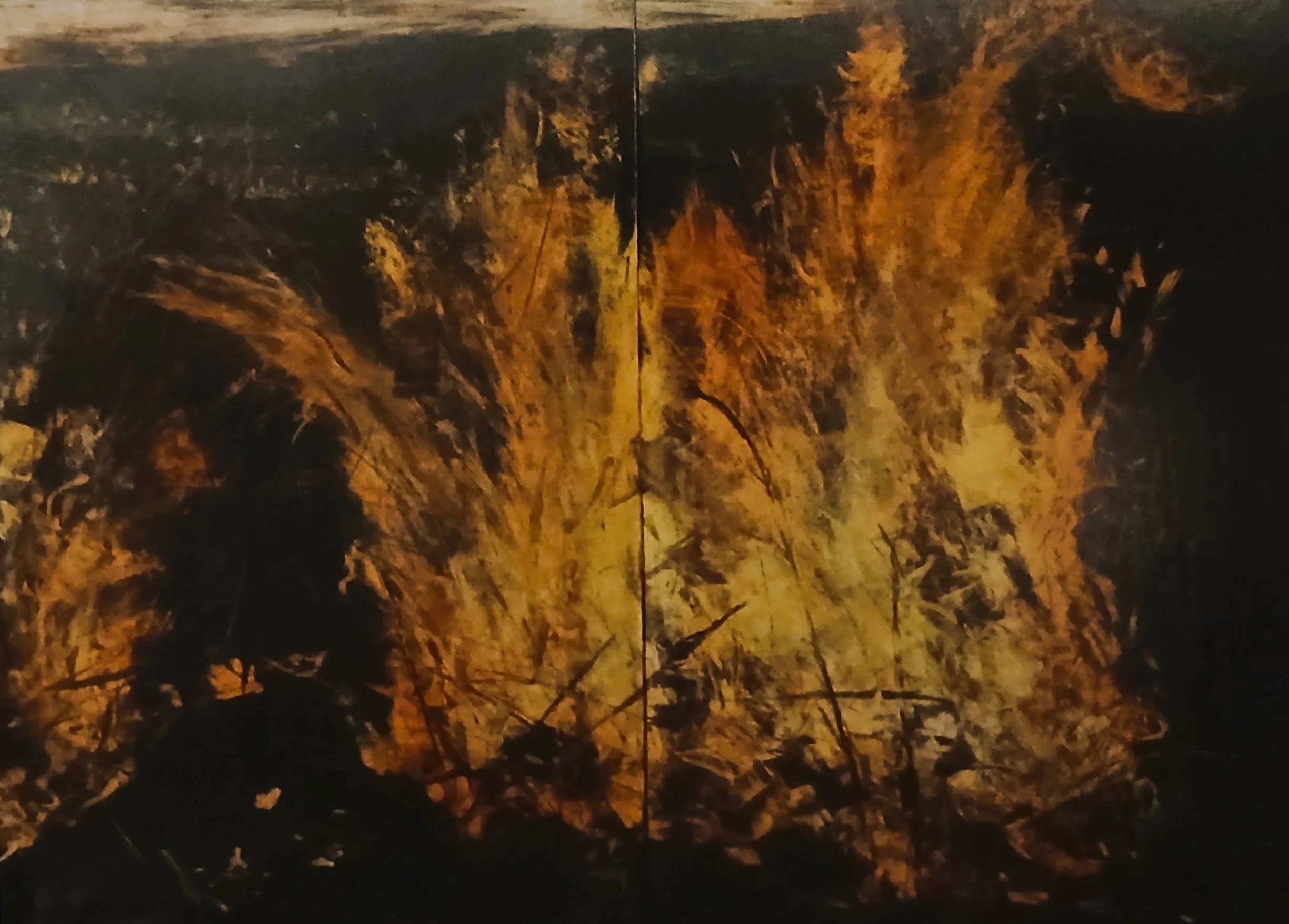

Kim Berman’s use of the landscape made great use of metaphor in motif but always reflects the people. Her Sunflowers in Mourning prints were created during the height of the HIV /AIDS epidemic in South Africa when official policy affected women left behind in rural village areas. A middle generation had passed away in large numbers, with grandmothers left shouldering the responsibility of caring for their grandchildren, while mourning the passing of those who had no access to appropriate care. These prints are mourning and conversely also celebrate the women of those communities - still the backbone of the nation, the resilient carriers of the flag - having waited so long, still looking forward with hope for a new tomorrow. Berman’s next major series leads directly into the idea of scorching fires. The Fires of the Truth Commission became a landmark series.

Landscapes of the Truth Commission series, 1999, Aquatint mezzotint

(Left) Tutu, Truth and the Path to Reconciliation,

(Right) “What we have hoped for will never be …”

(Left) “What the hell does one do with this load of skeletons, shame, and ash …” ,

(Right) Land and Bones

That idea that the Truth Commission bared all - and yet did not bare all, as we now know - raised further questions about the truth. For the first time, the TRC gave people who had been dispossessed of their proper lives or had lost their own loved ones to the struggle, the chance finally to tell their own stories properly, perhaps for the very first time. But what a scorched earth that left behind. Those revelations asked new questions about what the truth should become and how the truth should be followed up with justice.

In Berman’s 1999 A Decade of Work exhibition, The Fires of the Truth Commission and those images titled After the Fires, are always haunting. No viewer can unsee that scorched earth policy of trying to eradicate the histories of evil, while also revealing long suppressed stories of covert horrors in South Africa, committed in the name of government and governance.

These landscapes look too at the damage and required rehabilitation of landscapes resulting from mining, water pollution, conflict and misuse. We see more of Kim’s works raising her voice together with those of a group of collaborators. We should not forget the immeasurable contribution from the artist as an educator. Kim’s nurturing the careers of hundreds of young printmakers through membership of Artist Proof Studio, which she co-founded, is unparalleled. APS has offered great opportunities to a wider community who had never had access to such facilities. Graduates and colleagues from APS add their images to her own contribution, pointing to issues of concern, awareness campaigns and fundraising efforts. The education and training that printmaking with APS facilitated by Berman, has produced a respected group of artists now following their own careers.

It is impressive that while some reveal an echo of Kim's own work, they do not replicate it. Hers is the mind of an opinion-maker, and she is an illustrative leader of what printmaking can do to raise protest or document challenges and renewal in South Africa. Yet she has fostered teaching in a way which does not compromise artists’ making their own imagery and finding their own voices. Kim has a valuable role as a print teacher, not only in transmitting so much of her learning and skills acquired but also in transferring a kind of emotive understanding of working with the plate. Generous mentorship is a hallmark of Berman's practice.

Her fires and smouldering landscapes speak of those who had long-hidden truths to tell. Berman had worked towards the aims of the struggle for truth but also then dealt with the aftermath, which for some artists became rather complex. Others have written or spoken of the challenge of how to celebrate liberation, but also understand the scourge of their own memories, or collective memory, something which thoseFires of the Truth Commissionsuccessfully represent. First in capturing on a plate flames and smoke and a choking atmosphere; then how embers can die away but be reignited, laying open trauma and the damage which remains.

Panels 1, 3, 5, and 7 from the Fires of the Truth Commission, 2000, Monotypes,

in the Art Collection of The Constitutional Court

Her Fires of the Truth Commission works present these realities - the aftermath of the TRC - intelligently moved from words into imagery. They stand out for remarkably capturing that emotional and lingering memory of hardship. They are an unforgettable series. They will always capture that time.

It is helpful to understand the work of Sue Williamson, who powerfully presented people testifying and the people testified about, in her own significant series looking at the TRC, which she titled Truth Games. Williamson’s work shows people portrayed as accusers confronting the accused with the truth and arguments around the truths revealed.

In Berman’s work, the stories come out, but that truth is perhaps contested, produces new scars, lays bare some facts long forgotten, which people perhaps realise they had never quite buried; fires are reignited and acknowledge truths which remain buried or are burning still. The evolving landscapes grow, are burned, hacked at, damaged and finally, amid some clearing of smoke and ash, is the beginning of regrowth. There is the essence of hope in this work, even as it deals with grimness and continues to smoulder.

Charcoal stumps near Ventersdorp, 1995, drypoint with surface rolls

Excavation and Reconstruction, 2002, etching monoprint

Berman’s Truth Commission works are powerful and represent the best of her practice for me. Monotypes - not to be replicated in the same way as other prints, deeply felt and displaying nuance even when very graphic in style. She achieves being painterly even in exceptional printmaking. It is a fine achievement, not only in the subject matter, but through the materials and the way her plates are worked to manage those images, while retaining sensitivity and depth of emotion. That is indeed a salutary practice and one which marks a tribute to Kim Berman.

There are many of her works in museum collections, university collections and other teaching collections, but fittingly, most valuably, in the hallowed halls of the Constitutional Court of South Africa.