Sunflowers in Mourning

Sunflower fields were a feature of my early field trips in the 90s. The series on the Women of Madibogopane, women who are resilient agents in the face of oppression, economic hardship and drought, reference the extraordinary power of rural South African women organising in their communities.

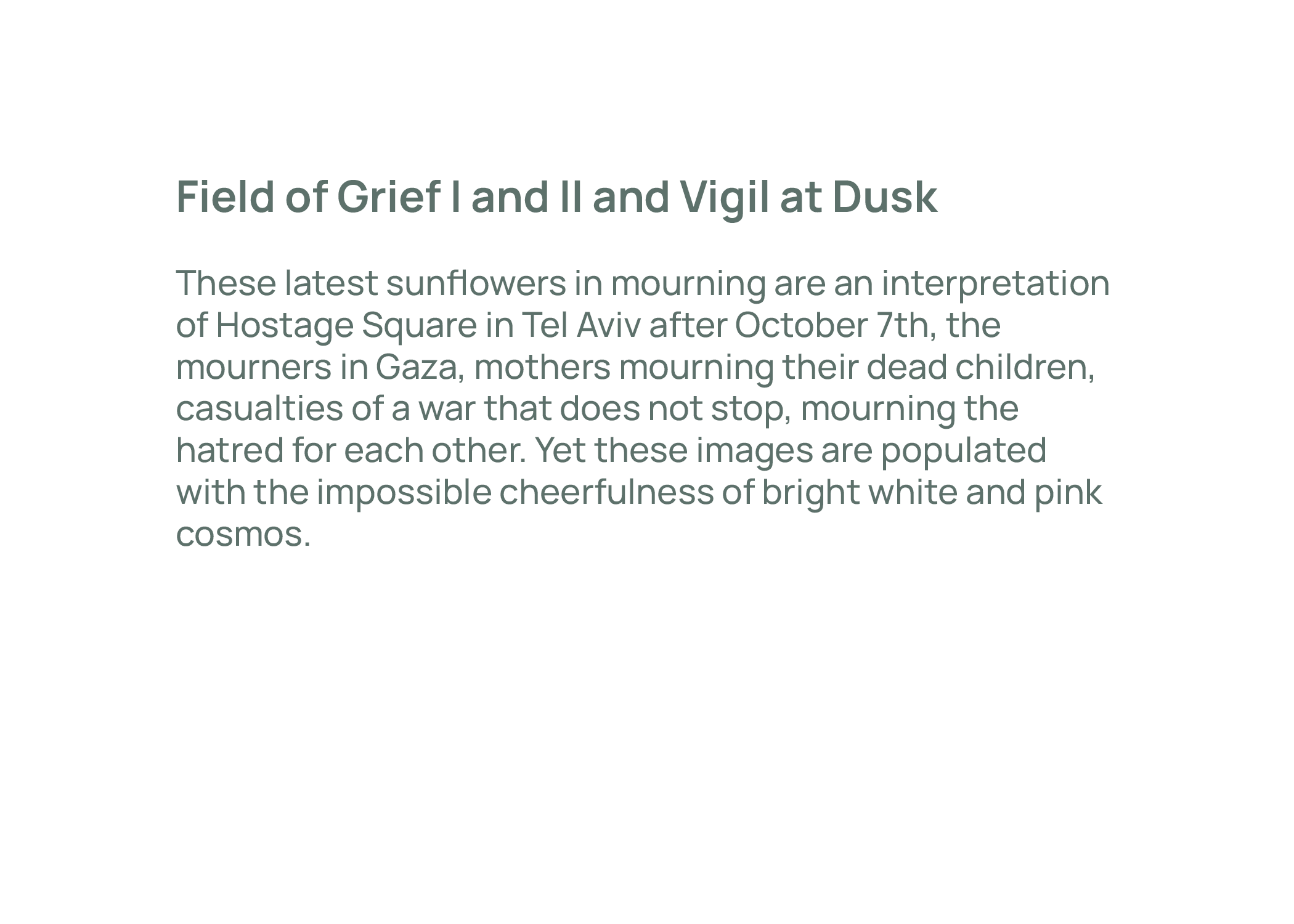

(Left)The Prayer of the Sunflowers (Centre) The Women of Madibogopane (Right) Mourners for Bev, 1997, Aquatint mezzotint

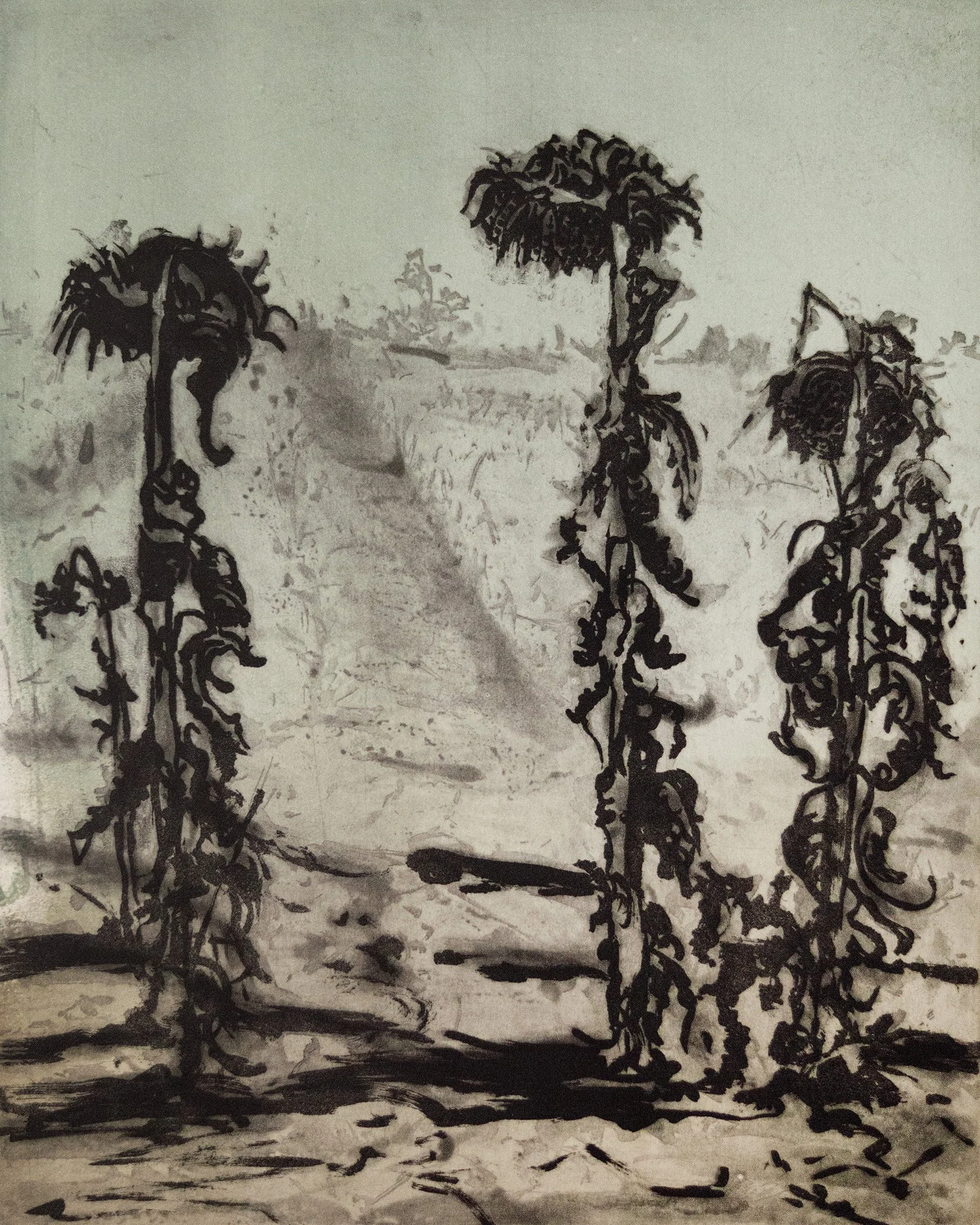

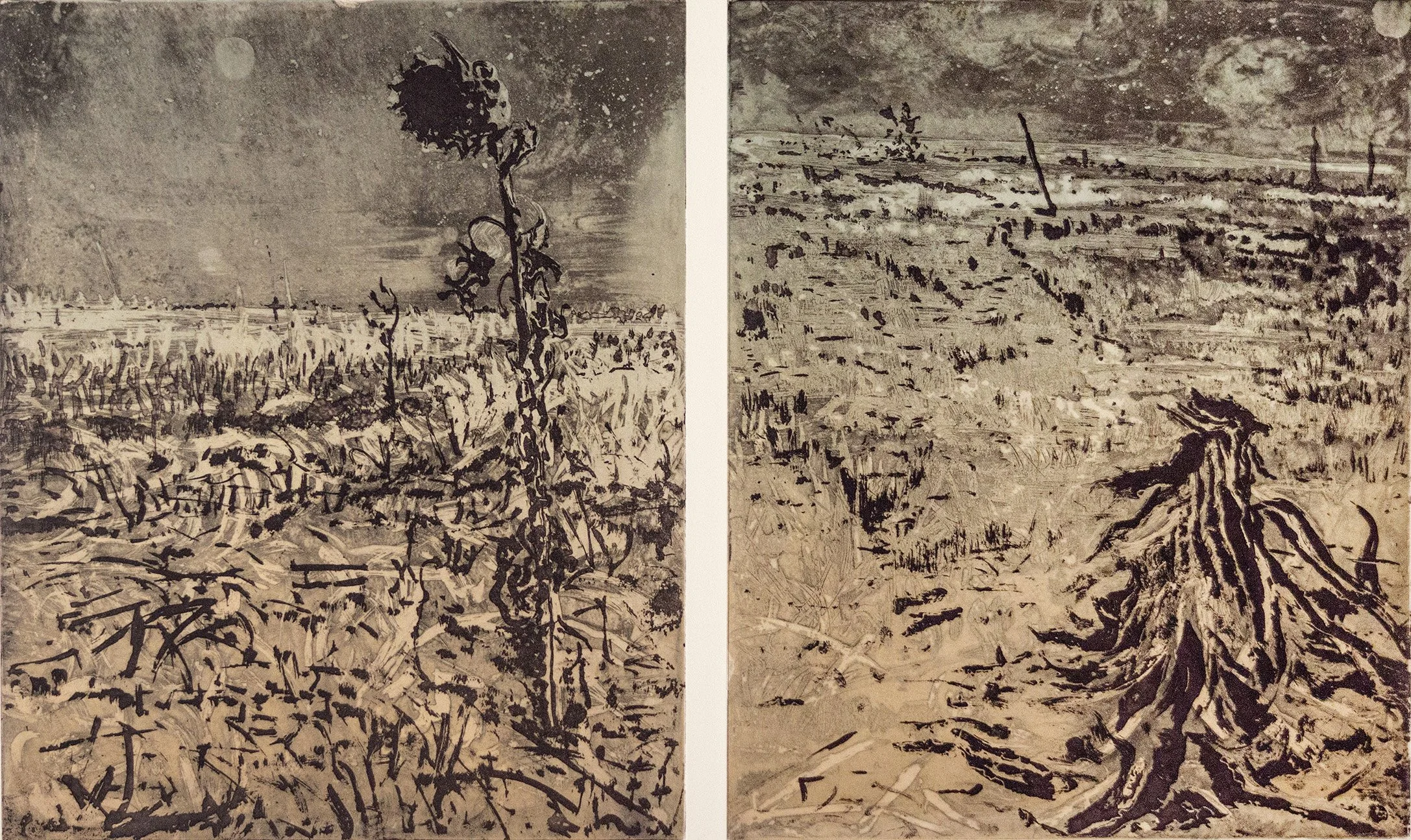

The year I was working on the series Landscapes of the Truth Commission, my cousin Beverly, with whom I grew up, passed away on an operating table from a botched routine surgery. For me, the sunflower fields became symbols for mourners expressing collective grief. And from that time, as an activist travelling across the country offering Paper Prayers workshops in partnership with AIDS educators, sunflowers represented the Mourners and the resilience of the movement. This led to the Sasol Wax project, where I was a finalist, and I used the opportunity to facilitate a communal project that involved 100 tribute portraits by APS members. I hoped that by paying tribute to a person each one of us has lost through AIDS, the contemplative process of etching would promote and hold safe futures and practices for the participants.

Sunflowers are a recurring theme and for my recent work, I find myself using the re-claimed and cut-up plates for a new series as rusty ghosts. Reworking them and including imagery of smoky fires, brings back the mourners from 20 and 30 years ago, like ghosts haunting the present.

The Universe in a Sunflower

Robyn Sassen

It takes an extraordinary kind of clarity of vision and perspicuity to be able to grab hold of a time-worn cliché and to change what it stands for. Radically and forever. Kim Berman has, with curiosity and courage, effectively done this all throughout her life and career. She’s turned ideas upside down and made them her own. She’s facilitated hope in people who thought they had none. She has challenged discourses to make them more relevant to the world as it stands. She has enabled phoenixes to grow out of an insurmountable sense of destruction. She has interpreted traditionally happy sunflowers to make you weep. And the sunflowers have represented a golden thread that has run through her more than 40-year career.

If you take a step back and consider in your mind’s eye, a field of conventional sunflowers, they’re entities which have, under the pens of illustrators, the mouses of film makers, the keyboards of songwriters and the eyes of those dealing in advertising platitudes, been used time and time again with their aggressive, implacable sense of positivity. They’re like a smiling face surrounded by yellow petals.

Since the early 1980s when she was a Fine Arts student at the University of the Witwatersrand, Berman has been invested in an understanding of the injustices of the apartheid regime, but further to that, of attempting to repair or redress great damage done to individuals by society; of attempting to expose great evils perpetrated in our country, our world. Her work was embedded in the charcoal that comes of burnt fields, the fire that comes of protest.

But then, there were the sunflowers.

With their big mop-like heads of yellow, and their faces black with seeds, these flowers, taxonomically grouped under the genus Helianthus Anuus, an important agricultural resource in South Africa’s Western Cape and North West Provinces, are about seeds and oil, which translates into money and resources. They’re not just pretty faces – they are farmed in this country, and they serve the economy and the country’s diet. There is a feral variety of them which is considered invasive and prohibited.

Survival (diptych), 2001, Etching

They also have a mythological hold on stories spawned by the west, which explains their English name as it holds onto their growth idiosyncrasies: A Greek nymph named Clytie, who the ancient storytellers told of, fell in love with Apollo, the god of the sun, but her love was thwarted. She was a lowly nymph, he an important god. All she could do was watch his path each day. Like Clytie, the sunflowers’ faces keep focused on the passage of the sun as it moves across the sky.

On Berman’s etching plates, the sunflower does something else. It exists in a political space where there is no sun to follow, and it droops its head in sadness. This oxymoron has become a metaphor that threads through an earnest and focused career which has been as much about empowerment and giving back as it has been about the collective energy of a printmaking studio. It’s been witness to atrocities and fire, to rebirth and reconstitution. The sunflower in mourning has, in Berman’s oeuvre, become a sub-theme that has always been present but never bolshy or maudlin in its domination of her horizons.

Bearing Witness, 2002, Sugarlift etching

Its anatomy is distinctive and eerily personified. The head is proud and big. Humanoid, implicitly.

It’s like a 1951 triffid, under the post-apocalyptic pen of John Wyndham. Or the kind of world-weary plants that with their deadening complexions and bits that have become ugly with mould and time, have slipped into the kind of freshness that drove Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings of the late 1800s.

But Berman’s sunflowers were never parts of a still life. They were always viscerally rooted in the ground. Even when the ground was filtered with the blood of murdered people or dark and dusty from having been burned and rendered into coal. Towering or cowering, with heads bowed in sadness or turned away in horror.

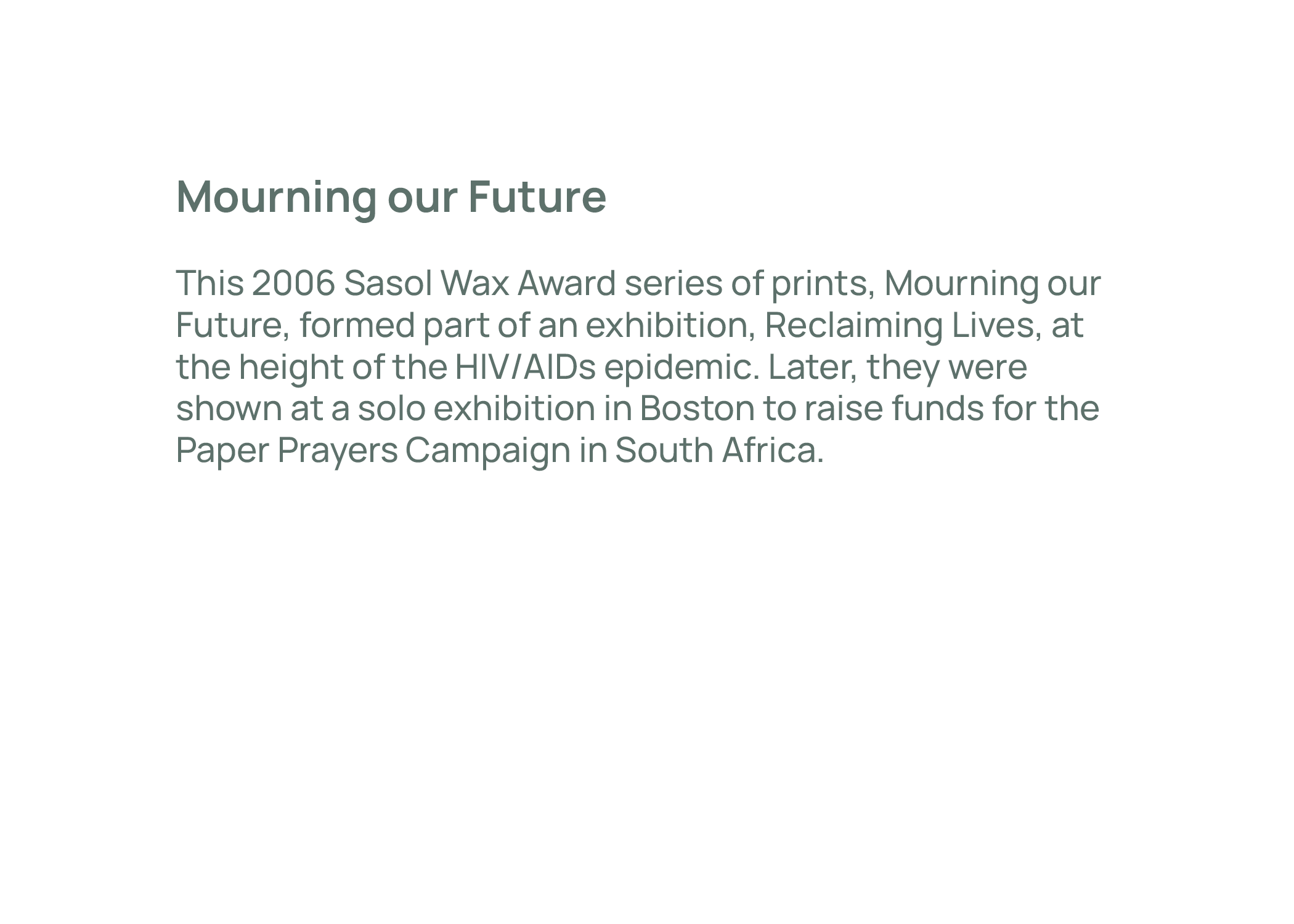

Over the years, her sunflowers have evolved. They’re no longer carefully rendered, with each ponderous leaf, each thick stem, each botanical follicle intact. They’re globby and emotive, with broken lines, deeply etched forms and a sense of rustedness. And in a sense, they’re more sunflowers than ever before. They’ve taken ownership of Berman’s landscapes as her vision has matured.

As part of Berman’s monotypes, they’re subject to the vagaries of what copper plates can do under pressure in an intaglio press, with inks of fiery orange and transparent whites and bold striations cut with a firm hand into smooth surfaces. They’re in prayer and standing in a field of grief, their heads collectively cast at the same angle of sorrow, that you, as a human being, with a head and a heart, understand because you’ve also mourned in that pose.

Rusted Ghosts I, 2024, Reclaimed rusted etched plate with added drypoint and hand colouring

Berman is an artist who has maintained her absolute focus on ideas that cleave with the current state of the world. In 2010, she wrote on the Artist Proof Studio website: “In my work, landscapes have always provided a metaphor for South Africa's transitions as a country: even in a poisoned, burnt, or smoke-filled landscape, the light on the horizon sparks the energy and hope for the cycle of change and imperative of renewal.”

Her sunflowers are not mythically evergreen. But they are rooted with a sense of eternal vigilance; witness to the surreal realities we face collectively, in the face of war and its discontents.

Field of grief, 2025, Etching on aluminium

Berman is also an artist, who alongside South African printmaking contemporaries of the ilk of William Kentridge (b. 1955), Dominic Thorburn (b. 1958) and Diane Victor (b. 1964), were born and raised in a world where the almost surgical rules surrounding the rigidity of printmaking were taught. It was also a world dirty with political violence; and social and political activism rapidly grabbed at the hearts of these young artists. What resulted was an extraordinary balance between the medium and the message – and these printmakers, who understood, respected and emulated the pristine value of a well-made print were able to bring their angry socio-political values to the press. This gesture was akin to the series of war etchings made by artists of the ilk of Francisco Goya (1746-1828) and Otto Dix (1891-1969), in confrontation of completely different wars in completely different eras.

Indeed, the peak of anti-apartheid activism in South Africa coincided with the peak of apartheid violence and legislation. Much visual material grew out of the process, within the realm of printmaking – silkscreening, to be precise. But many of these works have been lost in time or abandoned in art history as “one-liner” gestures, made in outrage, rapidly printed in makeshift studios – or kitchens – clandestinely posted on trees at night, and oft ripped down by the powers that be in the morning, before anyone had a chance to see them.

They became almost gratuitous gestures for the artists, like a bunch of thousands of flowers which were placed across the road from Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto on 16 June 1986, the tenth anniversary of the Soweto Uprising, in memory of children killed by the apartheid regime.[1] These flowers were rapidly stamped out of existence by the police, before anyone got to see them or understand the gesture.

Like tombstones from afar, or a crowd of people frozen in time, Berman’s sunflowers become ciphers to a turning world, bruised and battered though it may be with fake news, destructive political agendas, bare-faced lies and massacres of innocents.

Characteristically, Berman’s work grows in spirals. Her ideas are allowed to morph into one another, bridging long stretches of time in which she isn’t physically making work, but lecturing. A cycle turns, a teaching sabbatical shifts into place and the etching plate has become a vessel for a monotype, the field of bereft and furious women has shifted to look like one of flowers; the sunflowers are threaded through with cosmos.

It was the late Fine Arts Professor Alan Crump (1949-2009), who in 1980 was the youngest academic ever to take on the mantle of head of an academic department at a major South African university (Wits), who reworked the idea from the Romantic poet William Blake – of the universe being apparent in a grain of sand – in his teaching focus. He taught that a true artist is always curious, always critical, reads voraciously and has a multitude of rich knowledge and opinions, but as time passes, is someone who has the maturity to narrow their subject matter, to a rendition of a simple object, which becomes the language and the distilled cipher of everything. For French Impressionist painter Claude Monet (1840-1926), it was the haystack and the cathedral at Rouen, in Normandy. For Italian artist Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964), it was the same forms of a still life. Again and again. For Kentridge, it has been a coffee pot. For Berman, it is the simple, complex sunflower.

[1] This is an excerpt from a story called ‘These Flowers are for You’, written and self-published by Geoff Sifrin in 1988.